I have been an artist all my life. But ever since immigrating to Canada 18 years ago, and beginning studies at an art college, I have struggled with contemporary art and where I fit into it.

What I think of as contemporary art is not necessarily simply “art being made today”. In the 20th century, a lot of experimentation and redefinition took place, resulting in some art practices that I personally find ridiculous, bewildering, absurd, lazy and downright fraudulent.

It is beyond the scope of this post to make a more specific and concrete critique of contemporary art. The reason I bring it up is to say that as an artist, I had to sit down and figure out what kind of art animal I wanted to be. The thing about being an artist now is that it’s not at all a given as to what that means. Artists in industrial and post-industrial countries have a greater freedom to define their professional arena than they ever did in the past. It’s a great thing, but it is also a thing that can disorient artists at the start of their path, particularly if the artist in question doesn’t fit into the mold of visual art as it has been defined by mainstream art institutions after the 1970s.

What I came up with was this:

1. I don’t agree with the obsolescence model of art, meaning, with the idea that innovation is the most valuable and urgent task of any artist. I am not interested in art that is new, in its format or technical construction. I am interested in art that is unique, rich; art that has something to say; art that gives an eloquent and compelling voice to the way its maker sees the world. That kind of art is new by definition, regardless of whether its technical execution and format is based on a thousand-year-old tradition or on the latest iteration of a computer language. Art doesn’t have to be new. It has to be good.

2. The art I love the most is Western art – the painting, drawing and sculpting traditions of European civilizations. It’s not because I think that other types of art are lesser, or uninteresting. Western art is what I respond to most strongly from my guts, and what gives me the most pleasure as a viewer. It’s also the art of the places I come from. The two facts are probably linked, but in any case, even after seeing all manner of other art, paintings, drawings and sculptures of a realist and figurative nature are my strongest source of creative nourishment. Unfortunately, this source also comes with a package of problems.

In the 1970s, everyone in capitalist countries’ universities woke up to the fact that Western civilization is steeped in sexism, racism, colonialism and class oppression. Since that is the case, the art of this civilization is in many ways shaped by sexism, racism, colonialism and class oppression, because those things shaped the minds of the artists as well as the production and distribution of the artworks.

This critique was excellent, thorough, necessary and long overdue. But the 1970s were a decade of excess, and a lot of people went further than that and concluded that the art of the European civilizations was nothing but sexism, racism, colonialism and class oppression, and on top of it all, like, totally last month and bad-retro, and therefore had no value at all aside from being an instrument of oppression, and neither did the very activities of making paintings or drawings.

I don’t agree. First, I believe that the amount of oppressive crap on the canvas is directly proportional to the degree that the individual artist is an oppressive asshole. A lot of artists within the European traditions were humanist philosophers, consciously working to overcome the evils of their society. Some of those artists were even female, or non-white, or poor! There were also lots of simply decent people, with empathy and conscience that served to mitigate the way the evils of their society shaped their perceptions and beliefs. I believe that some of the things on the canvases are a contribution to healing the souls of the viewers rather than injuring them further, and a powerful, transcendent contribution at that. Western art has problems, but problems are not all it has.

Secondly, I think that the activities of making paintings or drawings are extremely necessary and fantastic, and that people have an intrinsic need to both make them and look at them. I am 600% sure that I am one of those people.

3. Therefore, what “being an artist” means to me is making paintings and drawings that involve human beings, objects and environments as their subjects, using the language of realism to do so.

In some ways, it is a relief to set these parameters, but in others it means I have a lot of work to do not just on the “how” of this kind of artmaking, but on the “what”. As in, what kinds of images do I want to make? As a self-proclaimed heir to the European art tradition, I have to deal with all aspects of that tradition, including the sexism, racism, colonialism and class oppression.

The critical thought that deals with those vile things exists on two levels, social and individual. On the social level, volumes and volumes have been written about them, and lots of intelligent and progressive people have given them time and thought. Even most recently, Cat Minou has marvelled at the way Tintoretto’s colours sing the beauty of the female body – a true female body with a belly and hips and not the starved pre-adolescent we are presently expected to be – and at the same time, the way he dehumanizes the women he portrays because in his pictures, they are nothing but bodies, bodies that don’t even have a response to being raped! Because the other fun part about Western art is how it’s all rape, rape, rape, rape, rape. Daphne, Europa, Danae, Lucretia, Ravished Nymph #1701. Can we have a break from rape, for maybe five minutes? Alright, here is some Annunciation. Sure, Mary was impregnated without her knowledge or consent, but it was to bring forth Jesus! Jesus is worth it! Plus, she is totally cool with the whole thing! And so is Joseph, and he was her husband!

In addition to the macro-critique, though, an individual, personal journey of critical thought is involved in addressing and transcending the crap aspect of Western art – how much the individual artist sees and notices it, and how they go about not making a further contribution to the crap aspect in their own work. In this respect, I think I have a lot of work to do, both with the sexism and the racism.

I’ve read a mountain of feminist art criticism, and being a woman with brains, I’m generally alert to sexist cultural bullshit, but I have also had a lot of formative experiences that conditioned me to accept being devalued and turned into an object as a normal course of events. It’s something I have to be alert about both in daily life and in my image-making.

As for racism, I have a huge, long way to go. Like many white people who have a conscience, I consider racism evil and wrong, don’t want to be part of the problem, and want to be part of the solution. Like many white people, I am also blind to what is called systemic oppression and privilege. Racism permeates every structure of our society and every particle of our culture, to the point where it becomes like water, and therefore invisible to us, the fish. It influences and shapes us as *conditioning*, as brainwashing. For people of colour, that means fighting racism not only outside, but keeping at bay the kind of internalization that causes a person to accept being devalued or turned into an object as a normal course of events. For white people, it means consciously and frequently thinking about racism and the various ways it’s present in the culture, and despite our best intentions, in our perceptions and actions.

People of colour have the issue of race shoved into their face 24/7 and our social environment makes it impossible for them to just be an individual, at any given time, for race to be beside the point and not on the horizon. One of the ways in which racism is evil is this sheer inescapability, the way it has to be dealt with every single time a person of colour opens a book, turns on the TV or leaves the house, let alone applies for a job or a mortgage. As a white person, I can look at Gaugin’s cool use of line and colour, and suspend thinking about how he portrayed Polynesians in patronizing and dehumanizing ways. A person of colour standing next to me at a museum and looking at the same painting can’t suspend, because she is patronized and dehumanized in the exact same way daily, because she is standing in an institution that until recently, denied her entry as anything other than a (naked) model, because she is the one being directly insulted by Gaugin as surely as if he is still alive and leching away at brown teenagers.

White people don’t have to live with this gauntlet or constantly fight against a sick deluge. And since we don’t *have* to think about it, we don’t. Not always because we are assholes. Sometimes, because thinking about race, racism and our daily, ongoing complicity in it, is painful and disturbing, and makes us ashamed, and deserved shame is not a nice feeling and takes emotional resources to confront, and meanwhile there are bills, and work, and errands, and the car broke down, and we have other sources of oppression such as sexism that do get shoved in our face 24/7 and get bumped to the top of the mental queue, and on and on and on…

So even the best-meaning of us have a natural tendency towards obliviousness. But as an artist and as an artist who is white and portrays people, I think it’s urgent for me to think about racism and how to make images that don’t end up being racist. Because I can help what I am conscious of, like not being disrespectful to the people I encounter, but I can’t help unconscious racism, which will most surely show up on the canvas as everything unconscious will, until that unconscious racism is made conscious, addressed and changed through awareness and knowledge.

I asked a media analyst and African-American journalist/blogger Harry Allen about what I can do in this regard. His suggestion was so simple, it made me facepalm: study the analysis on the subject, which is out there in droves. So much so that it’s silly that I haven’t done a lot of reading or studying of the history and writing of Black people, or thought very deeply about what the world is like for people whose skin colour is not the colour favoured by the dictatorship of race. Where I did get thus far is discovering very smart and thought-provoking blogs, such as Harry’s own Media Assasin Blog, Racialicious, Resist Racism and Womanist Musings.

Where it comes to the -isms of evil, the problem baggage of European art, I have a lot of thinking and a lot of *seeing* to do, of looking at the world and at the inside of my own head with eyes that are maybe wiser and more awake than the ones I have been using. In my studies for this past year, I have gotten a good way towards figuring out how to express what I want to express in my paintings and drawings. As to what I want to express, the answer will evolve as I do, but it is important to pose the question so that I can make a conscious choice as to which aspects of my artistic heritage I will give continued life.

Sometimes, artists, by which I mean me, like to moan about how it’s ever so difficult to make a living as an artist. Sometimes, in response, life does something that makes further moaning completely untenable!

Sometimes, artists, by which I mean me, like to moan about how it’s ever so difficult to make a living as an artist. Sometimes, in response, life does something that makes further moaning completely untenable!

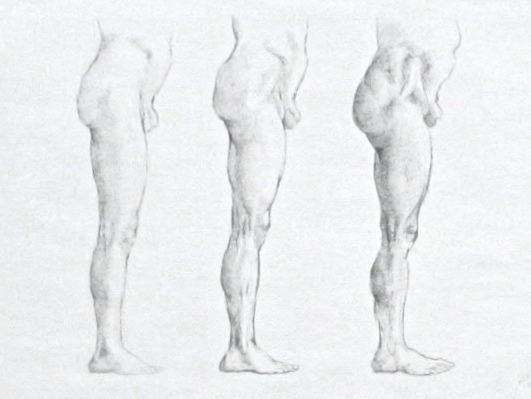

This fabulous leg bonanza is an exercise we did in Rey Bustos’s Analytical Drawing. Rey has taken to calling me his groupie, and perhaps this accusation is somewhat grounded in reality. In the spring term, I took his 3D Anatomy/Ecorche class, in the summer I took his 2D Anatomy, and now I’m taking Analytical Drawing to top it all off. Not only that, but I elbowed my way into the Analytical class as one of only 3 part-time students, because this course is in the full-time program, and I had to

This fabulous leg bonanza is an exercise we did in Rey Bustos’s Analytical Drawing. Rey has taken to calling me his groupie, and perhaps this accusation is somewhat grounded in reality. In the spring term, I took his 3D Anatomy/Ecorche class, in the summer I took his 2D Anatomy, and now I’m taking Analytical Drawing to top it all off. Not only that, but I elbowed my way into the Analytical class as one of only 3 part-time students, because this course is in the full-time program, and I had to